Understanding Redshifts

- Frequency Shifts

- Redshift and Blueshift

- Cosmological Redshifts

Part 1: Frequency Shifts

To understand what a redshift is, how about a music analogy.

Let’s say instead of light, each star produces sound. Some stars produce a C Major chord, made of the notes C, E, and G.

Notice there’s a gap of 3, and a gap of 2. You could say the "code" for this chord 10001001

Other stars produce an D Minor chord, made of the notes D, F, and A.

Notice this time, there is a gap of 2, then a gap of 3. The code for this chord is 10010001.

Now, you’ve discovered a new star, and it doesn’t make a C Major or D Minor. It makes this chord.

This is a new chord. Is it a new kind of star? Nope.

The gaps between the notes in this star are 3 and 2. It's code is 10001001, the same as the C Major star.

This isn’t a new kind of star. It’s the C Major star shifted up. All the notes are shifted up an equal amount.

How could a star’s notes get shifted up?

One reason is the Doppler effect, which we can hear in the horn of a moving car.

When the car is sitting still, and honks its horn, let’s say it comes out as a middle C. The frequency of this note is 261.626 Hertz. That means, a sound wave from the horn reaches your ear 261 times every second.

If the car was speeding toward you, blasting its horn at 261 Hz, the car gets closer to you between each sound wave, meaning the crests of the waves get closer together, reaching you at a higher rate.

If the sound waves reach you at 277 times per second, you will hear the car horn at a C#.

Anyone sitting in the car, however, will be moving at its speed, meaning the sound waves don’t get any closer together relative to the passengers’ ears. To them, the horn is still in tune at middle C.

Going back to the star, we can understand how the notes in the chord are shifted up: it's the Doppler effect of the star moving towards us.

A star that sounds like C# Major is not a new type of star. It’s just a C Major star, shifted up one note by traveling towards us. A D Major star is also a C Major star, but shifted up two notes.

The farther the notes have been shifted up, the faster the star must be traveling toward us.

The same works shifting down. If we discover a C# Minor star, for instance, we'll know it's a D Minor star (code 10010001) shifted down.

The lower a star’s chord is shifted, the faster it is moving away from us.

Part 2: Redshift and Blueshift

Stars don’t actually produce sounds though. They produce light. But sounds and light both have frequency, and the Doppler effect applies to both.

So let’s replace the musical notes with colors. Red has the lowest frequency, and blue has the highest frequency.

This should actually be read as the opposite of the music analogy. Instead of the line indicating which notes should be played, the lines in the color spectrum indicate which frequencies are missing.

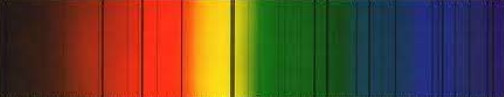

Different elements like oxygen and sodium and calcium absorb light at different frequencies. So depending on which frequencies are missing when we analyze a star’s light, we can tell what the star is made of. Here are the sun's actual absorption lines:

And then by looking at the gaps in between the absorption lines, we can tell if it’s moving away from us or toward us, and how fast.

If the star is moving away from us, the frequencies are shifted down, and the colors move to the red side of the spectrum.

That’s called red-shift.

If the star is moving toward us, the frequencies shift up, and the colors move to the blue side.

That’s called blue-shift.

Some stars are moving away from us, and some are moving toward us, and some are pretty still relative to us. So whether a star is red-shifted or blue-shifted is somewhat random. It just depends which way it happens to be moving, which is called its peculiar motion, because it is particular to one star..

Part 3: Cosmological Redshifts

Galaxies can be red-shifted and blue-shifted too. They are just groups of stars after all.

Some galaxies are blue-shifted, which means they’re moving towards us. But there are surprisingly very few blue-shifted galaxies, and they are all among the closest galaxies to us.

Nearly all the galaxies we observe are red-shifted. And the more distant a galaxy is, the more red-shift it has.

We understand the red and blue shifts in Zone 1. Galaxies have their own peculiar velocities, like stars do. But they are insignificant and overtaken by the redshift that happens in Zone 2.

These redshifts are referred to as "cosmological redshifts", and were not expected at all. One would have assumed the pattern of random red and blue shifted galaxies continues.

Is cosmological redshift caused by motion, the same as the red and blue shifts in Zone 1?

Or something else?

Go back to Fixing Hubble's Law